Finding Mukti and Shakti in London Archives

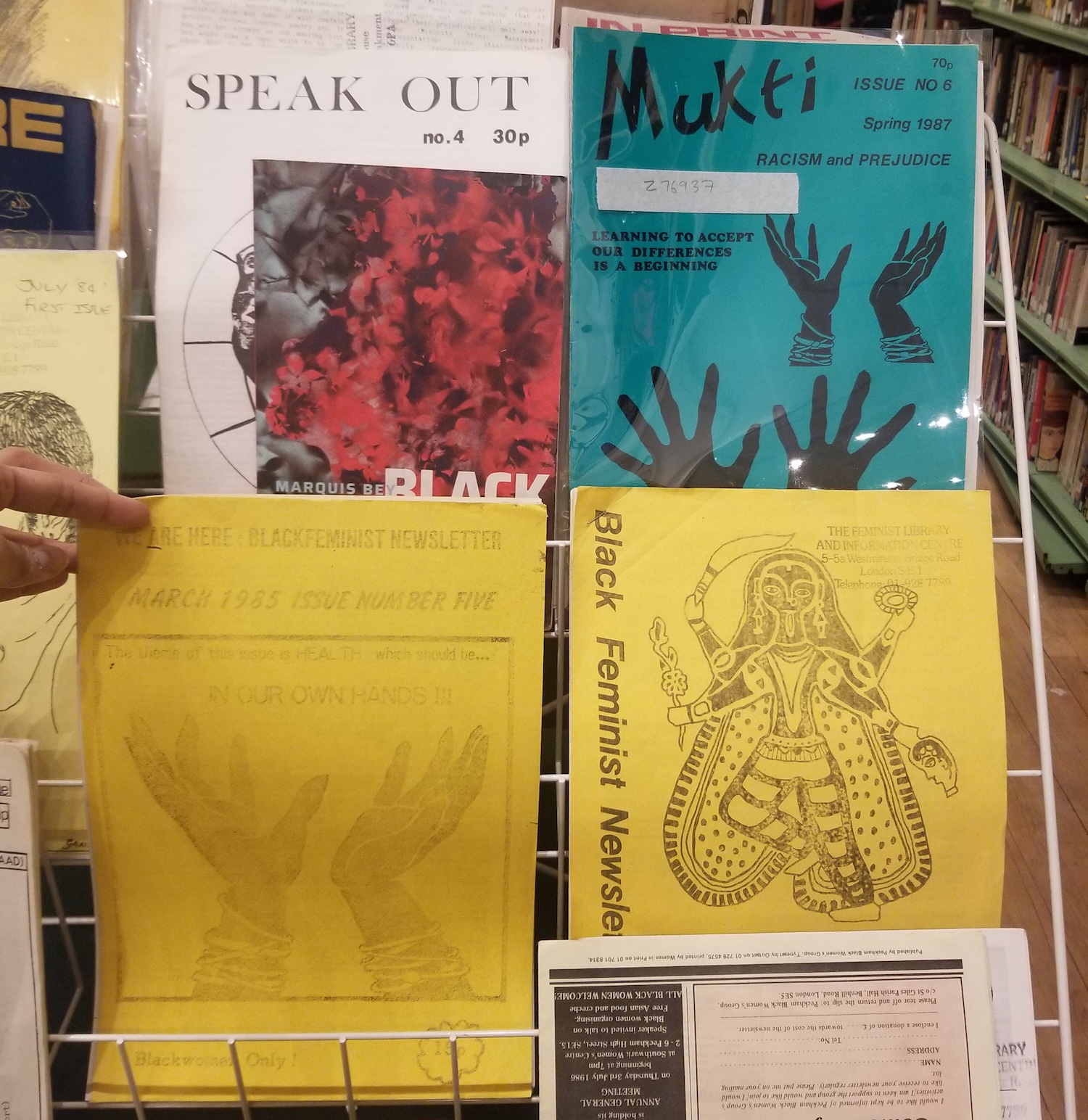

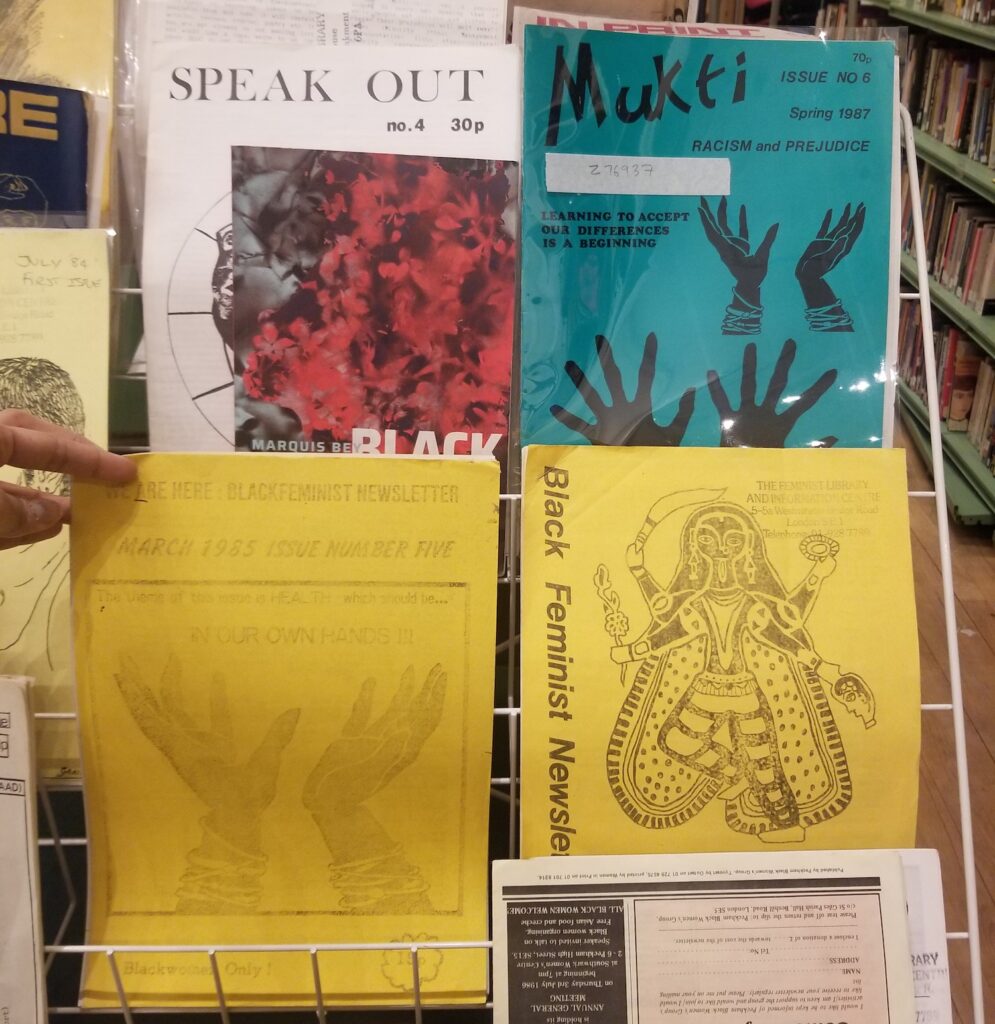

In November 2024, supported by a Sam Fox School travel award, I traveled to London, UK for the first time for a conference. Towards the end of this trip, I squeezed in an excursion to The Feminist Library, which has been collecting and archiving feminist literature since 1975. Alongside books and zines, their holdings include about 1500 periodical titles, “the largest collection of feminist journals, magazines and newsletters in the UK.” Reaching the library 30 minutes before their closing time, and immediately overwhelmed by the scale of their collection, my attention was drawn towards three items in a small display of a selection of their periodicals and newsletters.

First, the cover of Mukti, from Spring 1987, with an illustration of two bangled hands, both name and illustration clearly signalling that this was for South Asian women—mukti means liberation in many South Asian languages. Second, the cover of We Are Here: Black Feminist Newsletter, from March 1985, carrying the same bangled-hands illustration as Mukti. My confidence that the illustration was for or about South Asians wavered, as I puzzled over how it was related to a newsletter about Black feminism. Adding more questions was the third item, another issue of Black Feminist Newsletter from 1984, with an illustration of a goddess deity that could be Kali. My creative practice and research as an illustrator focus on feminist praxis, visual culture, and South Asian identity. Seeing these three periodicals together set off a series of thoughts in my mind. I considered my initial certainty these illustrations were either made by or for South Asian women. I wondered why these images appeared where they did, especially the one that repeated across publications. I was struck by the impulse these women had to write, illustrate, print, and distribute these periodicals. Perhaps these shared illustrations were one way that these feminist groups supported each other and developed networks. As printed artifacts they were clearly a means for South Asian and other women in the UK to find community and organize systems of care and advocacy. My brief visit to the library sparked a new interest—I knew I had to return.

I made my way back to London in August 2025, supported by the Newman Exploration Travel Fund award. In the months between my two visits, I learned more about South Asian feminist and queer groups in Britain and the periodicals they produced. In Amrit Wilson’s Finding a Voice: Asian Women in Britain (Daraja Press, 2018), first published in 1978, I read about the histories of South Asian migration to the UK, and the way South Asian women grappled with patriarchy, domestic violence, casteism from within their communities, and racism and sexism from their new home country. Building off Wilson’s book, Churnjeet Mahn, Rohit K. Dasgupta, and DJ Ritu’s Desi Queers: LGBTQ+ South Asians and Cultural Belonging in Britain (Hurst, 2025) opened me to the history of queer South Asian organizing in the UK, with a focus on the queer group Shakti (meaning power), and their newsletter Shakti Khabar. Both books began to answer an initial question and a hunch I had at The Feminist Library. In the 70s and 80s, immigrants from the former British colonies organized themselves under the self-identification of “political Blackness.” “Black” at that time meant any person of African, Caribbean, or South Asian origin. So, many community groups formed both around specific cultural identities and also came together under the umbrella of “Black groups.” This explained why the image of Kali was on the cover of the Black Feminist Newsletter and solidified my guess that these different groups interacted and worked together through their newsletters. While I’d originally intended to study as many issues of Mukti, Black Feminist Newsletter. and Shakti Khabar as possible during my trip, my new understanding of the concept of political Blackness in the British context also dramatically expanded the kind of material I was searching for and where I could find it. Ahead of my travel, I compiled a fairly intensive dataset of British South Asian feminist and queer periodicals, posters, and other printed ephemera that I’d located in five different archives—The Feminist Library, London School of Economics (The Women’s Library and Hall-Carpenter Archives), the British Library, Bruce Castle Museum, and the Bishopsgate Institute. Unfortunately, I discovered close to my trip that the volunteer-run Feminist Library would be closed through August, so I was unable to spend time in their collections.

Prepared with more knowledge and context on this second visit to London, I began to notice things in a new light. The South Asian workers I encountered at Heathrow airport reflected the long history of Punjabi, Gujarati, East African, Sylheti, Bangladeshi, Pakistani, and Eelam Tamil migration to the UK. The Overground train I took to my friends’ home had been renamed the Windrush Line, as part of an effort to have London Overground lines reflect the city’s diversity. The Windrush Line honors the Black immigrants who arrived in the UK aboard the Empire Windrush in 1948 from what was then the British West Indies. The people I saw around the city who looked like me–on the tube and buses, in parks, at markets—were there because of their countries’ relationship to Britain as its former colonies. The area I stayed in, Shadwell, was home to South Asian seamen in the 19th century. In 1936, Shadwell residents, along with trade unionists, communists, Jewish groups, and others, successfully clashed with a fascist march through the East End, in what is called the “Battle of Cable Street.” Today, the area has a majority Bangladeshi population. (Shadwell is part of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. I didn’t know it yet, but I would find the Tower Hamlets Council logo on many of the materials I was rooting through in the archives.)

My first week in the archives began at the London School of Economics (LSE). I had to quickly learn how to manage my allotted time, the ambitious scope of material I wanted to review, and my desire to dawdle and do close-looking in the archive. I had a fairly short list of materials to request at LSE, and anticipated being done in a day. I instead needed three days there, even requesting an additional day (which they were able to accommodate, luckily), and also using the backup appointment I’d scheduled for my second week just in case. One part of my need for this extra time was figuring out a note-taking system on the fly so that I could keep track of my observations and impressions against the hundreds of photos I took. The other was that I kept finding new material that I had not expected. This element of discovery in the archive was a surprise, but also continuously deepened the scope of my search.

After two days in LSE’s archives, my next stop was the British Library, to study issues of Mukti, a periodical produced in the 1980s by South Asian women in Britain who organized themselves as the Mukti Collective. As the national library of the UK, its collections hold over 170 million items (170,000,000 in case you needed to see that with all the zeros). Being a public library, access to the British Library itself was much easier than LSE. The scale of their holdings, however, and the fact that their systems are still hobbled by a massive 2023 cyber-attack meant that accessing material itself in the library was quite frustrating. After many hours of not being able to locate the issues of Mukti in their holdings, scrambling to try and schedule last-minute appointments at another archive that happened to have the same material, I was finally handed a small bundle of Mukti, solely because of the help of extremely supportive librarians who made calls, sent emails, and tracked down what I needed. I’d read that the women who produced Mukti also simultaneously published each issue in English, Urdu, Punjabi, Hindi, Bengali, and Gujarati, to reach as many South Asian women as possible. I had a surprise waiting for me—among the full run of English issues of Mukti at the British Library, there is also a Hindi version of issue no. 1. One of the challenging things in an archive is the expectation for it to be complete, or “historical coherence,” as scholar Mimi Thi Nguyen says in her essay “Minor Threats” (2015). So, although I was delighted to have the chance to compare the Hindi and English issues and thoroughly wished that I could see copies of each issue of Mukti in all the languages it had been published, I also had to accept the “incompleteness” of the material in front of me. I closed my first week in archives at the Bruce Castle Museum in Haringey, a collection I learned about through reading Desi Queers. Bruce Castle Museum holds records, registers, printed material related to Haringey and Haringey Council, where queer Black community groups like The Black Lesbian and Gay Centre and Haringey Black Action operated from. Since the collection I wanted to peruse here was relatively smaller, compared to the other archives, the archivists welcomed me with six boxes—all of their material related to Black and South Asian activism in Britain.

By my second week in the archives, I felt like I had cultivated a streamlined system for requesting, reviewing, and taking notes. I even finished my final day in the LSE archives ahead of schedule! I moved on to the final archive on my list—the Bishopsgate Institute—and the place with the most number of items for me to review. Bishopsgate Institute’s special collections and archives hold a wide range of material, including one of the most extensive collections on UK’s LGBTQIA+ history, politics, and culture. At Bishopsgate, I experienced the most relaxed archive of all the ones I had been to. I did not need to make an appointment, I could sit at any open table, and I did not have to wait for specific retrieval hours. The archivists here watched me exclaim (audibly) in surprise at the scale of old posters I’d requested, letting me handle them carefully with no folders, sleeves or gloves in the way. This ability—to touch and hold flyers, periodicals, posters, leaflets that queer and women South Asians had made and held decades earlier—felt like time travel in a sense.

Over two weeks in these archives, my notebooks filled with notes on around 150 items (posters, periodicals, flyers, postcards, letters, meeting notes, reports) and I accessed many, many more. In reading the words of South Asians before me, seeing their illustrations, and physically touching the same materials they did, I felt connected to these people who found ways to organize networks of care and community well before the internet opened the world up to anyone with access to it. They were artists and community organizers. Evidence of their intersectionality was in much of the material I went through. Many people, whose names I saw in different council meeting records and credits in newsletters for writing and illustration, participated in both women and queer groups, in both Black and explicitly South Asian groups. This allowed them to communicate concerns between groups and advocate for each other.

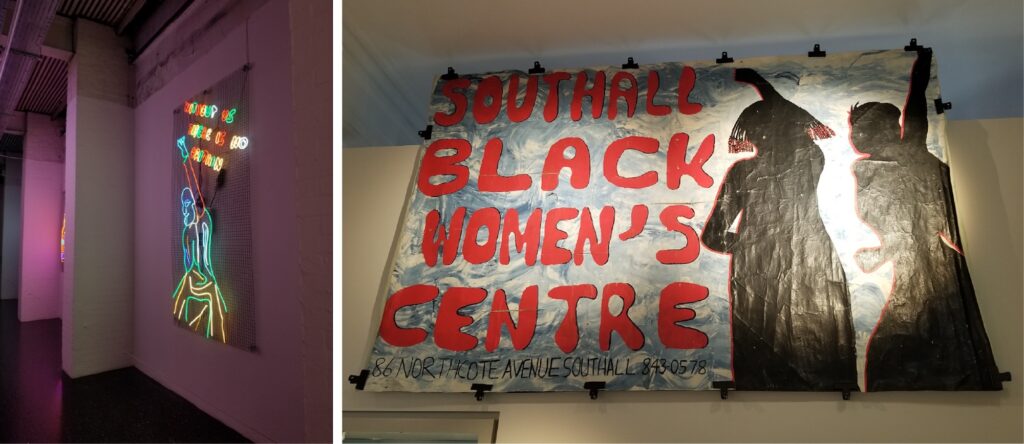

I ended my trip with visits to two exhibitions recommended by friends. The first, Connecting Thin Black Lines 1985–2025 at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), brought together the original artists of The Thin Black Line, a groundbreaking 1985 group show of young Black and Asian women artists at the ICA. One of the artists in this show, Chila Kumari Burman, was also a Mukti contributor. A neon installation by Burman at ICA titled Without Us There is No Britain (2020) referenced the cover of issue no.1 of Mukti. The second exhibition, Peoples Unite! How Southall Changed the Country at the Gunnersbury Park Museum, detailed the ways that the people of Southall, a largely South Asian suburb in West London, have contributed to social movements in the UK. Photos of DJ Ritu, one of the authors of Desi Queers, appeared in a gallery detailing the evolution of Southall’s Bhangra music and club culture. Elsewhere in the exhibition, I encountered Chila Burman’s work again, through a recreation of a mural she painted in 1985 with Keith Piper, titled Southall Black Resistance Mural, documenting the Southall community’s 1979 uprising against the far-right National Front. The gallery beside this held one of the first protest banners painted by Southall Black Sisters, a feminist group established in the aftermath of the uprising to advocate for the rights of Asian and Black women. Southall Black Sisters is still in operation till date, continuing to support minoritized women in the UK.

On more than one occasion in the archives and exhibitions, I found myself tearing up at the challenges and systemic problems these people navigated—much of which remains the same —and the audacious hope they nurtured for different circumstances. In the weeks after I returned from London, I noticed many Black and South Asian Britishers posting online about rising incidents of racism that echoed some of the first-person accounts in the Peoples United! exhibition. In September 2025, the UK saw both one of its largest anti-immigrant and anti-immigration rallies, and immediate counterprotests that challenged racism and bigotry. The time I spent in London on this visit has pushed me to consider more deeply how people can find and care for each other, sustain hope when it seems impossible to, and actively work together to build a world that everyone can thrive in.

Shreyas R. Krishnan’s research trip to London was supported by the Newman Exploration Travel Fund.