Religion and Resistance in Cold War El Salvador

I am deeply grateful for the support of the Newman Exploration Travel Fund award, which enabled me to travel in August to Colorado and El Salvador. My purpose was to research the intellectual history of liberation theology in El Salvador and to understand this history in its social and political context.

In the first half of this essay, I would like to tell you about this important and neglected chapter in the global history of the Cold War. Then, in the second half, I would like to share some of the archival documents that the NEXT Award enabled me to read and learn from.

Every document I examined deepened my understanding of this subject in some way. Many of them shook me profoundly.

Part One: Background

The 1980s are often seen as a period of Cold War thaw and détente, from the perspective of the conflict’s superpower protagonists. The view from Central America, however, was starkly different. In Nicaragua, the left-wing Sandinista movement, named after the earlier guerrilla leader Augusto Sandino, overthrew the long rule of the Somoza dynasty. Violence between the Sandinista government and the US-backed “Contra” rebels dominated the decade. Likewise, in El Salvador, a 1979 coup inaugurated a decade of military and social ultraviolence.

American involvement in the Salvadoran civil war is the rough inverse of its involvement in Nicaragua. In Nicaragua, the Ronald Reagan administration funded paramilitary forces bent on destabilizing the socialist government. In El Salvador, a bipartisan succession of U.S. administrations—the Democratic president Jimmy Carter as well as Reagan—funded the Salvadoran military and its post-coup junta government, aligned with the country’s oligarchy of agricultural elites, in its suppression of a socialist guerrilla force, the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN).

Then as now, El Salvador was a deeply Christian, and especially Catholic, country. When the civil war in El Salvador made major news within the United States, it was often because of state and state-affiliated violence against bishops, priests, nuns, and lay Catholics. The most infamous example is the assassination of Óscar Romero, the archbishop of San Salvador. Perceived as a theologically and politically conservative choice upon his appointment to the archbishopric, Romero’s views developed rapidly while in office, especially in the wake of the assassination of his friend, the priest Rutilio Grande, who worked to secure land rights for the Salvadoran peasantry. After Grande’s death, Romero himself began promoting the cause of land rights, as well as criticizing the violence of the government and demanding a dignified life for the Salvadoran poor.

In March 1980, Romero was killed by a drive-by assassin while delivering Mass in San Salvador, the capital city of El Salvador. His assassination was ordered by Roberto D’Aubuisson, the founder of the far-right political party ARENA, and the charismatic public face of the nation’s paramilitary death squads. D’Aubuisson was a frequent guest of honor in Washington, D.C., especially admired by Republican politicians and activist groups for his extreme anticommunism. In light of the US foreign policy establishment’s endorsement of D’Aubuisson, it is less shocking that the Salvadoran military’s rape and murder of a group of Catholic women in December 1980 — three of them nuns, and all four of them US citizens — resulted in only a brief pause to Salvadoran military aid under the Carter administration.

The killings of Grande, Romero, and the US nuns are not chance occurrences. Instead, the Salvadoran military and its affiliated death squads saw a significant faction of the Catholic Church as a major ideological threat deserving of military extinction. As Penny Lernoux reports in her book Cry of the People, in the early years of the civil war, buildings in El Salvador were frequently graffitied with the tagline: “Be a Patriot — Kill a Priest.”

How did the political dimension of the US evangelical movement come to align itself with the executioners of priests and nuns? (As I learned in the archives, the official radio station of the Salvadoran military, Radio Cuscatlan, included the US televangelist Pat Robertson’s program The 700 Club as part of its regular broadcast schedule.) The answer is the rise, and ensuing suppression, of a social movement across Latin America known as liberation theology. Spurred by the late 1960s “Vatican II” reforms across the Catholic Church as a whole, leaders and priests across the Church began thinking more assertively about social conditions in Latin America, in relation to the social teachings of the Church. They published critiques of the economic development theories of scholars in the Global North, which emphasized a given country’s GDP to the neglect of its quality of life for the majority of the population. They also formed “base ecclesial communities,” local social organizations attached to the Church that encouraged their members to interpret the Gospels for themselves. Under the sign of liberation theology, intellectuals and the uneducated alike took Christ’s love of the poor as the starting point for social theory. What would a society truly built on such a love look like?

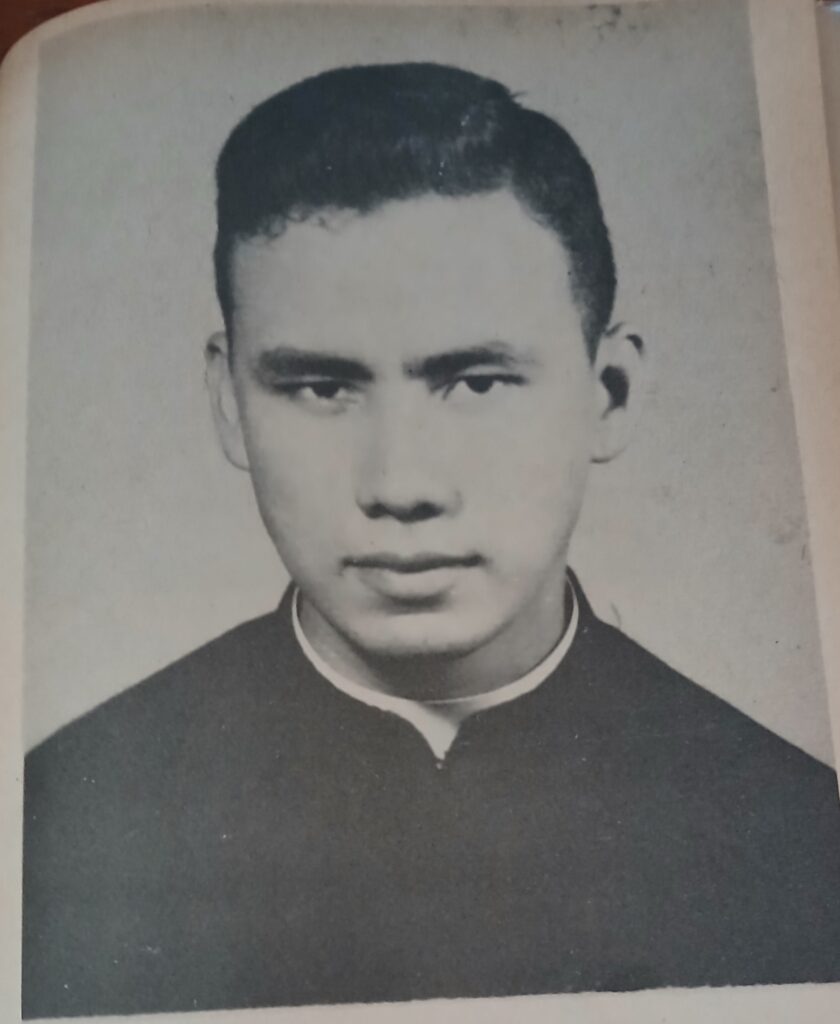

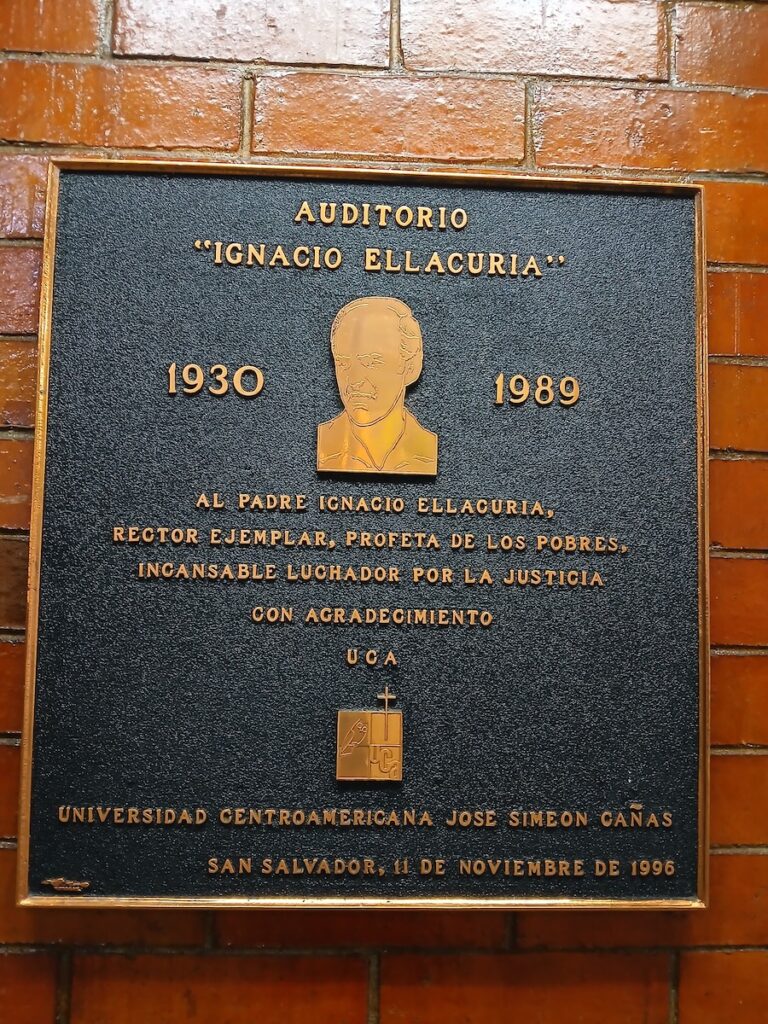

It would doubtless be very different from the El Salvador of the 1980s. This conclusion was vocally declared by the Jesuit faculty of the University of Central America – José Simeón Cañas (UCA), located in San Salvador. Founded and led by its rector, the philosopher and theologian Ignacio Ellacuría, UCA became the major intellectual center of liberation theology in Central America.

(Right to left): Commemorative plaque and portrait of Ignacio Ellacuría, S.J., on the campus of the University of Central America – José Simeón Cañas.

After an initial period in which some UCA faculty collaborated with the junta government on small-scale land reform projects, UCA became a steady target of death threats and bombings in response to its criticism of government suppression. The UCA faculty were demonized as communist sympathizers. Its Jesuit faculty in particular, several of whom were Spanish-born, were xenophobically demonized as outsiders, presumptuously meddling in Salvadoran affairs. The campaign against Ellacuría and his colleagues culminated in November 1989–one week exactly after the fall of the Berlin Wall—with the mass murder of six UCA Jesuits, including Ellacuría, on the campus of the university. Two employees of the university were also murdered, both of them women. The murders were carried out by the Atlácatl Battalion, a counterinsurgency force trained directly by the United States Army.

Part Two: Travels

My research interests as a graduate student often involve the history of ideas. Three of the six slain Jesuits of UCA — Ignacio Ellacuría, the psychologist Ignacio Martín-Baró, and the political scientist Segundo Montes — were highly productive scholars. They are quintessential examples of the “organic intellectual”: intellectuals who combine scholarly rigor with close connection to the needs and organizations of the broad public, especially the poor. My interest in intellectual history is the reason that, although I find the story of Latin American liberation theology compelling across the board, I am especially interested in intellectuals who identified with that movement and who were persecuted because of it. My goal is to understand them not only as victims—although the Jesuits of UCA certainly were that—but as thinkers, with interesting things to say.

To that end, my itinerary had two parts. I began with a trip to Boulder, Colorado. The University of Colorado houses one of the largest sets of collections on earth about the Salvadoran civil war. Their collections include: the archives of Salvadoran human rights organizations active during the war; North American activist groups seeking to raise awareness of U.S. support for the Salvadoran government; and a large trove of documents recently donated by the National Security Archive, a non-profit based in Washington, D.C., dedicated to researching and indexing declassified documents of the U.S. security state. Collectively, these collections constitute a sweeping picture of the social effects of the war, including its brutal consequences for the demonized sector of the Church.

Unlike many humanities scholars, I have escaped infection with what Jacques Derrida famously termed “archive fever.” As a result, I do not have a long and deep history of intensive archival research. Perhaps this is not saying much, then, but my week with these collections was the most emotionally taxing week of research I have conducted.

For example, I spent significant time with “Torture in El Salvador,” a Spanish-language report of the Comisión de Derechos Humanos de El Salvador (CDHES), a non-governmental human rights organization that took inspiration from Romero and was frequently targeted for repression. The 1984 report documented the brutal and illegal conditions in the notorious La Esperanza (Hope) Prison. Remarkably, the report was authored in secret by five CDHES analysts while they were incarcerated in prison. The report was somehow smuggled out of the prison, translated into English, and sent to a long list of major American newspapers by members of the Marin County Interfaith Task Force, a US-based group with an archival collection at UC Boulder. Of all the newspapers that received the report, only one ran a thorough article about it, despite multiple prisoner testimonials in the report alleging involvement by US military officials in the administering of torture at the prison.

The remainder of my trip was in San Salvador, spending my days burrowed in the library at UCA. The collections there offered more occasion for optimism. Though the library’s general collection is plentiful, the most valuable to my research was its “Salvadoran Collection,” which sets aside materials across disciplines that are about life in El Salvador and written by Salvadoran scholars. The collection included many out-of-print volumes published in the 1980s and 90s by UCA Editores, the university’s press, most of which are by UCA faculty from the period. For this reason, though it contains work in many other fields—such as an edited volume by Martín-Baró on the Social Psychology of War—the collection is a unique trove of academic theology by Central Americans during a major phase of liberation theology as a movement.

A favorite work of mine from the collection is Trinidad y liberación (1994) by Antonio González. In Christian thought, Trinitarian theology concerns itself with the nature of the Holy Trinity. By what process are its three persons somehow one? Is this process wholly mysterious, or partly knowable to human reason? What qualities does “personhood” entail, in the context of the Trinity? Because of its high degree of abstraction, Trinitarian theology is not a major genre of Central American liberation theology, which more often concerns itself with ethics and interpretation of the Gospels.

In his monograph, González seeks to wed the two. By taking the personhood of the Trinity seriously, González interprets the Trinity as an ideal vision of social life. Each member of the Trinity directs to its other members a perfect love, of the kind imperfect human creatures can only strive to achieve. The structure of the Trinity—a whole divisible into three parts—means that to contemplate the Trinity is to undertake a task of analysis: analysis being, at its most basic level, the attempt to understand something by inspecting its parts. God, who takes pleasure in being worshipfully contemplated, thereby encourages and fosters the practice of analysis. To me, this is a moving endorsement of the adventure of intellectual life.

I want to mention a couple of people I met on this trip, both of whom also gave me cause for hope. One of them is Ruben, the user experience librarian at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver. While I was in Boulder, I drove out to Denver to make use of Iliff’s large collections on liberation theology, as well as its collection donated from the personal library of Black liberation theologian Vincent Harding. On short notice, Ruben curated valuable items from across these collections that I would not have otherwise come across, all the while sharing a remarkable offhand knowledge of the founding of Iliff and other religious history in Colorado. His professionalism and personability are yet another example of the invaluable and often invisible work librarians perform.

I also want to mention Ernesto, a graduate of UCA and sometime lecturer there whom I befriended in San Salvador. Ernesto was born in 1980 and has personal memories of the UCA assassinations of 1989. His childhood recollections of the war, and his easeful knowledgeability about a wide range of other topics, are both things I am grateful for.

Over the weekend, I got the chance to visit the beach with Ernesto, about half an hour outside of the city. We took turns swimming in the ocean, while the other guarded our belongings. Sometimes, perhaps especially while traveling, ordinary moments strike you with an unusual intensity. I know this is a somewhat curious note to end on, but one of those moments happened to me while I was sitting on the beach, watching Ernesto swim. I grew up in a landlocked state and am very unnatural in the ocean; it was clear that Ernesto, by contrast, knew exactly what he was doing. There was an elegance and felicity to the way he held his body in the water, moving with the motion of the waves. His body was absorbed in play, in a kinetic negotiation with the ocean. After weeks spent inside my head with often grim archives, it was wonderful to watch such innocent and skillful pleasure. It reminded me that the earth is beautiful, and replenished my revulsion at politicized cruelty, which has denied to so many life’s simple gifts.

Nick Dolan’s research travels to Colorado and El Salvador were supported by the Newman Exploration Travel Fund.