400 Years of Women Printers: Elisabetta de Rusconi to Virginia Woolf

You may be surprised to learn that since the development of the printing press in Europe, women have been deeply involved in the printing and production of books. A close examination of books held in the Julian Edison Department of Special Collections reveals evidence of women’s active role in book production over the past 500 years. Dozens of pre-1900 books in the WashU Libraries’ collections name women as responsible for their production.

During the early modern period (1500-1800) tasks were highly gendered. Jobs included making type and ink (men), typesetting or placing each letter that forms the printing plate (women), inking and running the press (men), and sewing pages (women). Master printers were also responsible for raising and managing funds, selecting texts and how many copies to print, and running in-home shops.

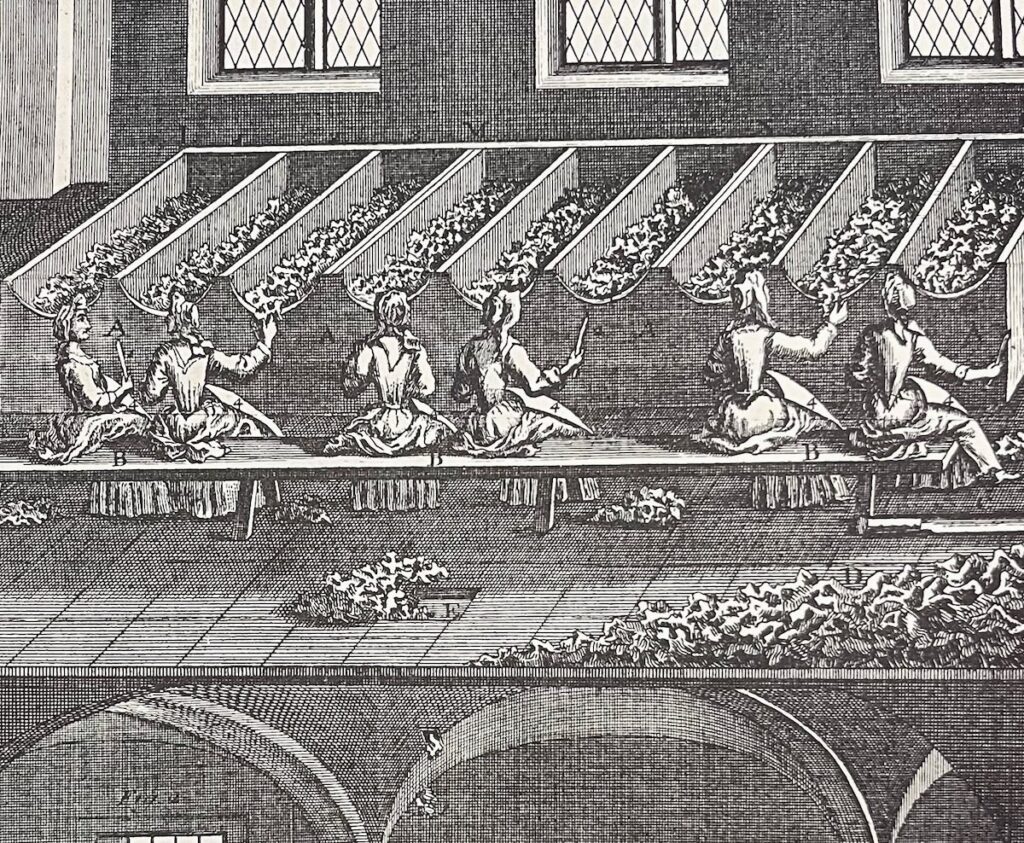

The one thing printers did not do was make paper. Papermaking wasn’t technically difficult, but it was labor-intensive. As with printing, the work was typically segregated by what was seen as suitable tasks for men and women. Paper was made from linen rags, and rags were considered women’s and children’s business. They would sort, scrape, and prepare rags for men to ferment and press into paper molds. Women would then clean, examine, and sort the sheets of paper.

By the mid-1800s, the Industrial Revolution was in full swing, and much of printing and bookbinding was automated. Folding, sewing, and feeding the printing press were jobs that still had to be done by hand. These tasks were seen as unskilled labor and thus women’s work. The big difference from earlier times was that women worked outside the home in factories.

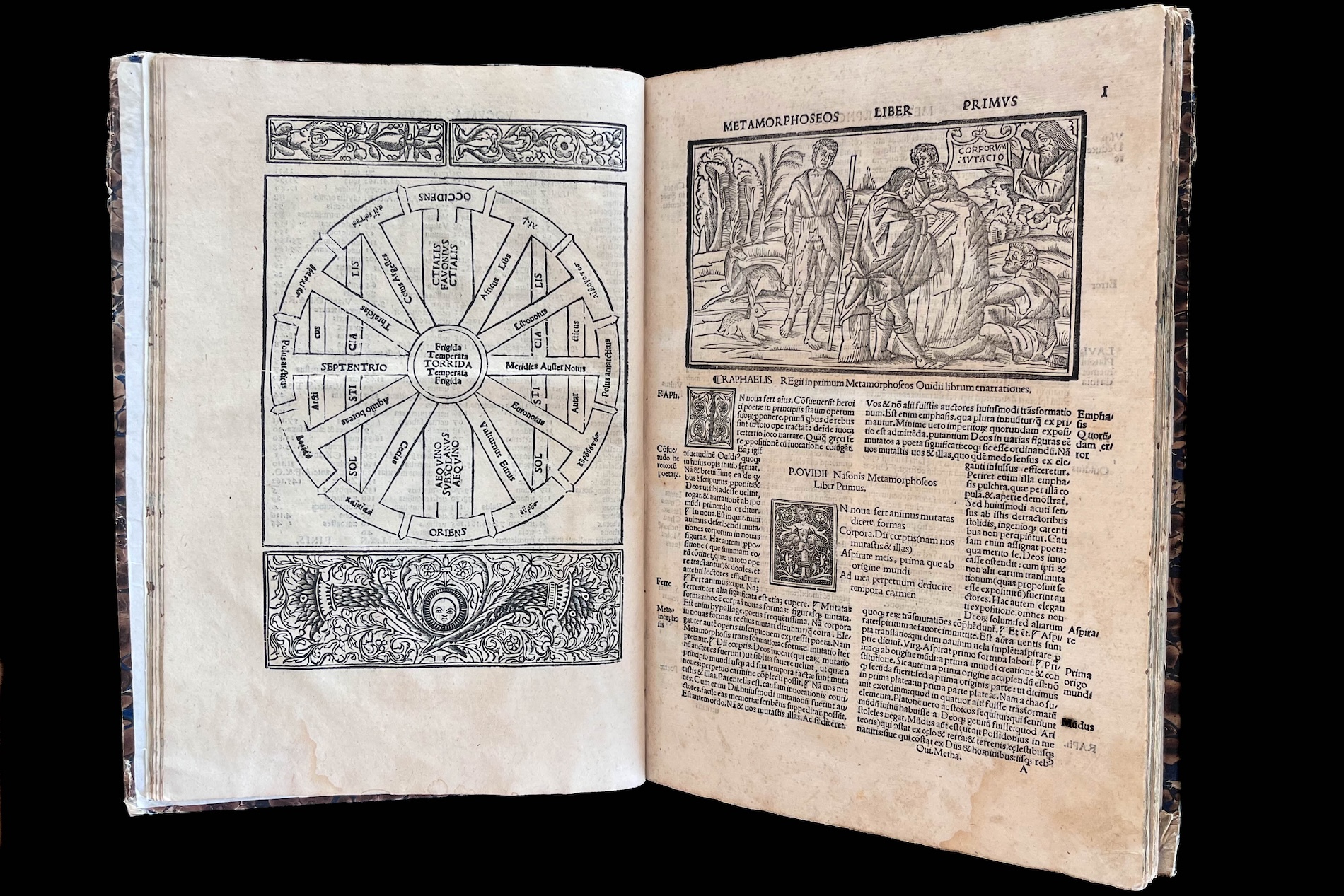

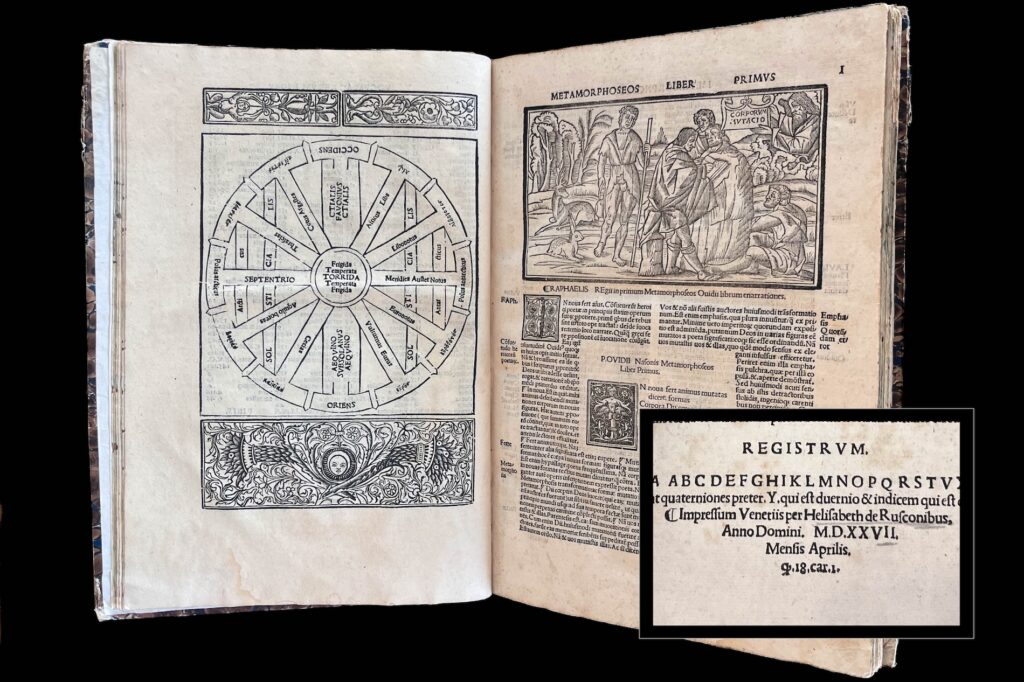

Learning about the active role women had in book production over the past 500 years, it’s no wonder there are also visible traces in WashU Libraries’ extensive Rare Book Collections. The Libraries’ earliest known example of a woman taking responsibility for the production of a book is hidden on the last page of a 1527 edition of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Her name only appears in the colophon, or final lines of the book, sometimes used to attribute responsibility. It reads in part “Printed in Venice by Elisabetta of Rusconi.”

Like so many women printers during her time, Elisabetta Rusconi née Baffo (active 1524–1528) took charge of the family print shop after her husband’s death. Ovid’s Metamorphoses was a popular classic text and widely published, but Rusconi’s printing is significant because, from page one (pictured), it shows significant skill at composing complex layouts.

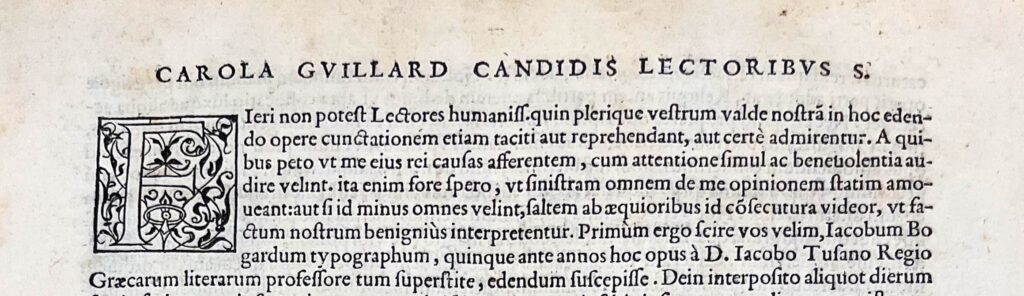

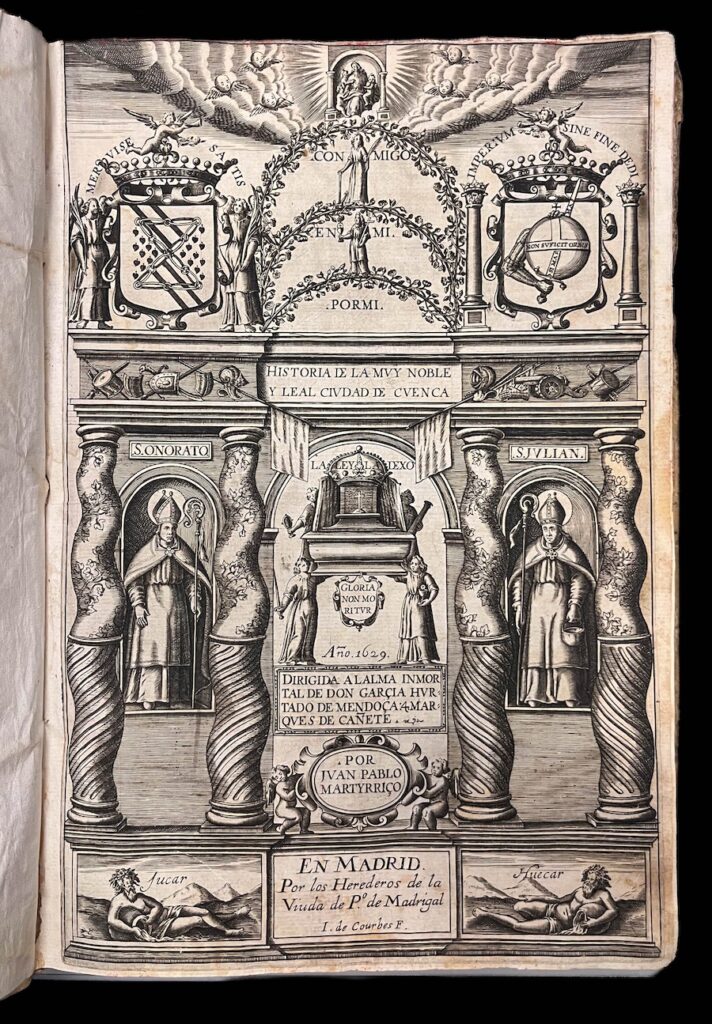

Although there are other examples of women naming themselves as responsible for printed works (Charlotte Guillard, died 1557; Elizabeth Flesher, active 1670–1678; Elizabeth Whitlock, died 1698), it was much more common for women to identify themselves as “the widow of –”, such as the imprint “the widow Sebastien Huré.” This may have been for economic reasons. Printing was a risky endeavor that could require an entire year’s worth of effort before making any money back, so a trusted name was important to attracting business. Presumably that’s why María de Quiñones (died 1669) used “the heirs of the widow of Pedro Madrigal” for several years after inheriting her mother-in-law’s business. It may also be why Manuela Contera, (1722?–1805) went to great lengths to make it known that she worked out of her deceased husband’s actual workshop, unlike her sons. Her husband, Joaquín Ibarra Marín, was the most highly respected and innovative printer in Madrid and his death caused a major rift between his family for unknown reasons. The couple’s sons left to print under another master printer while Contera and her daughter printed under “the widow of Ibarra, his children and company” and later “the daughter of Ibarra.”

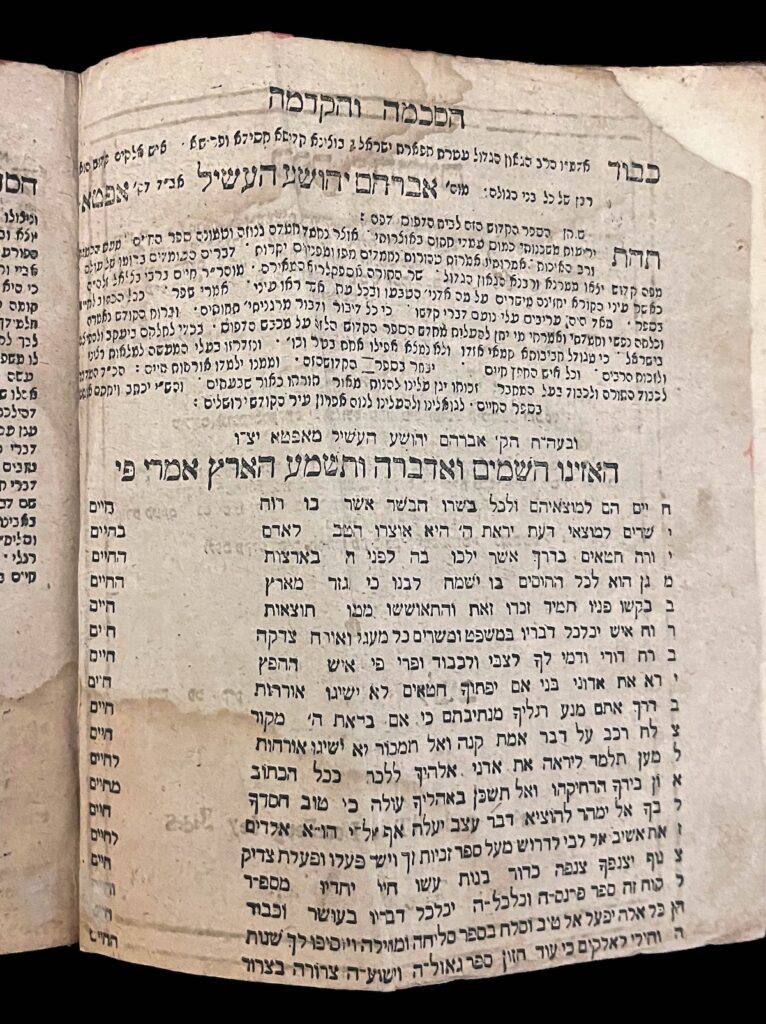

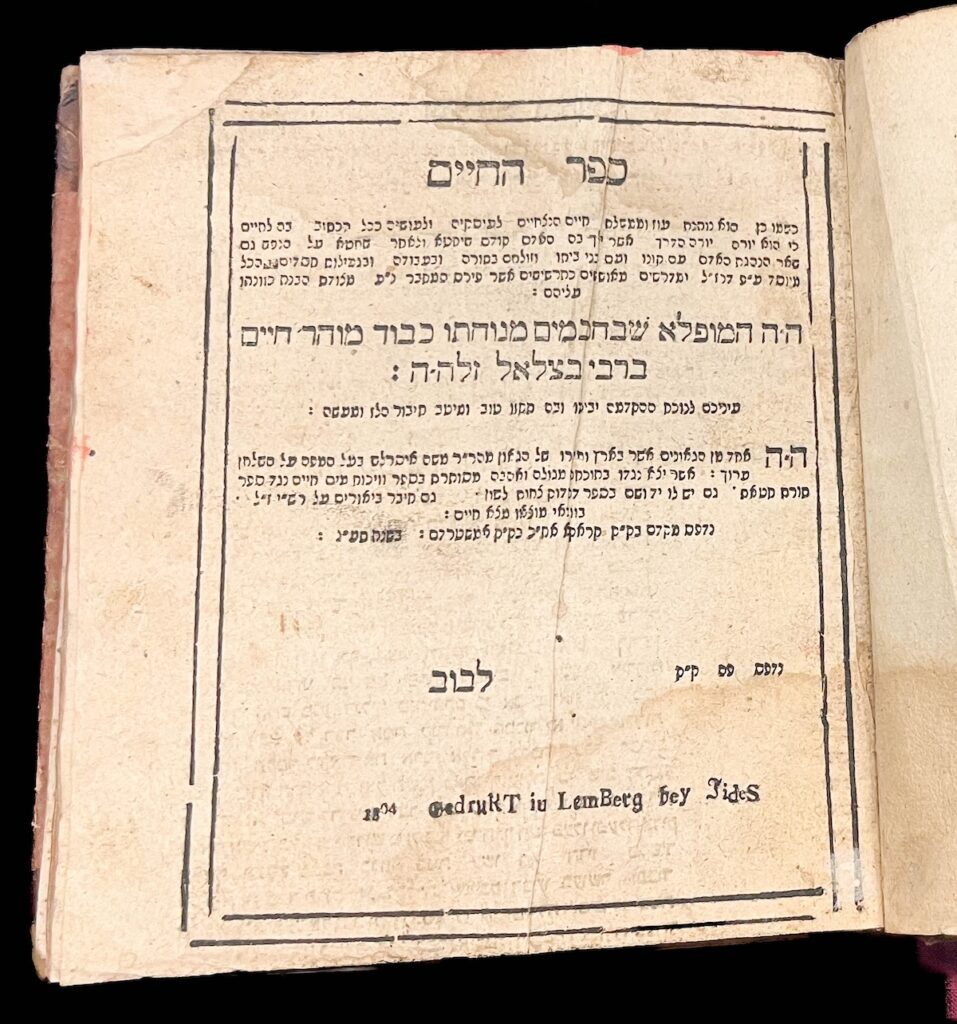

There is much evidence of Jewish women printing alongside their fathers and husbands, but Judith Rosanes (died 1805) is considered the first Jewish woman printer who printed commercially over a long period of time, over twenty-five years. Printing in what is now Ukraine, Judith states in plain German “1804 printed in Lvov by Jides” on the title page of Sefer ha-ḥayim / Ḥayyim be-Rabi Betsalʼel / ספר החיים / חיים ברבי בצלאל. On the next page, she printed an acrostic poem spelling her name.

Although many women like Judith make it clear they’re responsible for the printing of a book, more often, a closer look and background knowledge are needed to uncover a woman’s involvement. In the first American gynecological textbook, A Treatise on the Diseases of Females by Wm. P. Dewees, Lydia Bailey’s (1779-1869) tiny imprint, “L.R. Bailey, Printer,” is on the back of the title page. Using initials was common during this time, further obscuring women’s involvement. Bailey was, in fact, a prolific and well-known printer in Philadelphia. She claimed to have trained over forty men in typography over her fifty-year career. Many men who went on to have their own influential careers studied under her.

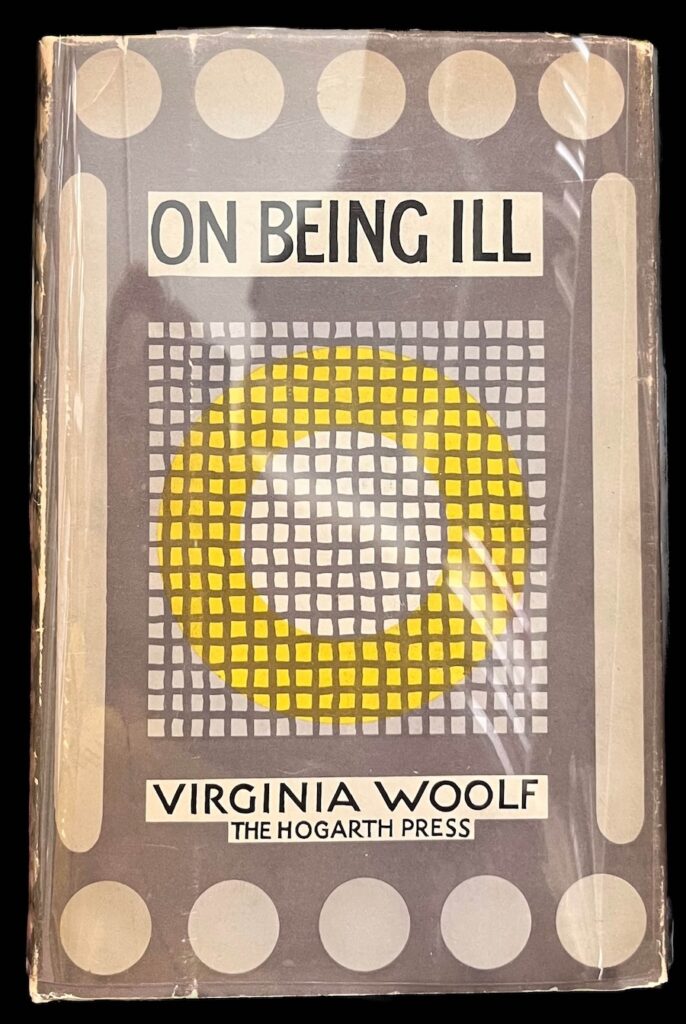

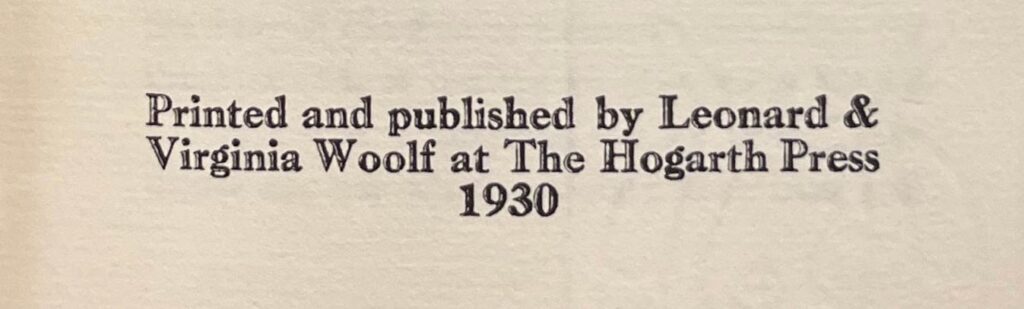

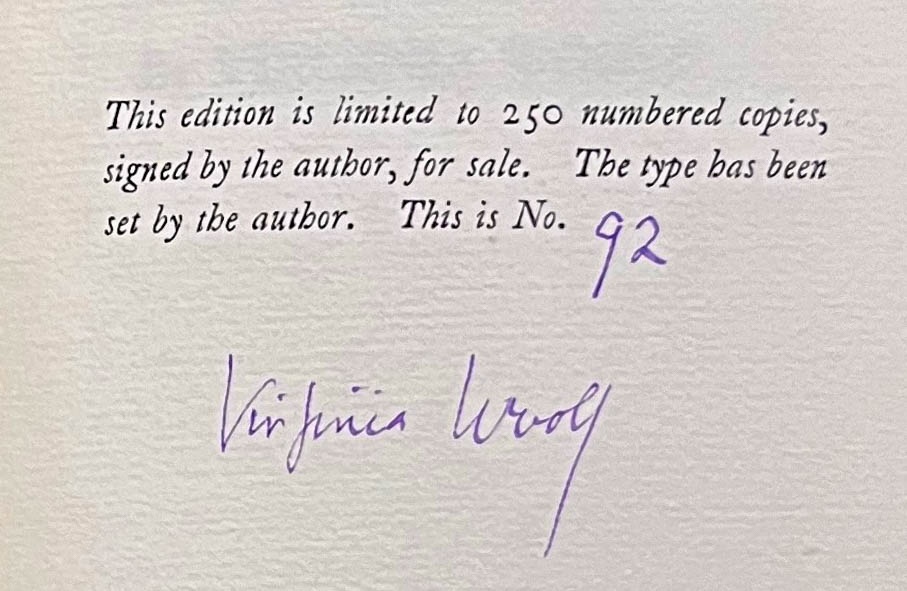

For the past 200 years, publishing has been done on a massive scale, but there have also been many private presses releasing limited-quantity, high-quality books. One such press was founded by the seminal author, Virginia Woolf (1882-1941), and her husband Leonard, in their dining room. The Woolfs published hundreds of titles under the name Hogarth Press, with Virginia typesetting and binding the books, and Leonard pulling the printing press.

The books named in this article–and 100 more printed by women between 1520 and 1920–are available for research in Special Collections. For more information, contact the curator of rare books Cassie Brand.

Further Reading

Baker, Catherine A., and Rebecca M Chung, eds. Making Impressions : Women in Printing and Publishing. Chelsea, Michigan: The Legacy Press, 2020.

Broomhall, Susan. Women and the Book Trade in Sixteenth-Century France. Women and Gender in the Early Modern World. Aldershot, England: Burlington, VT, 2002.

Hudak, Leona M. Early American Women Printers and Publishers,1639-1820. Metuchen, N.J.: Metuchen, N.J. : Scarecrow Press, 1978.

Karen Nipps. Lydia Bailey : A Checklist of Her Imprints. The Penn State Series in the History of the Book. University Park, Pa: Penn State University Press, 2013.

Schmidt, Ariadne. “The Profits of Unpaid Work. ‘Assisting Labour’ of Women in the Early Modern Urban Dutch Economy.” The History of the Family 19, no. 3 (2014): 301–22.