LGBTQ History Month Spotlight: Intertwined Lives

On exhibit through December 14, 2025, in Olin Library, Intertwined Lives explores how Cornelia L. Crow Carr and Harriet G. Hosmer—women from very different backgrounds—became chosen family to each other and found ways to lead unique and independent lives in the nineteenth century.

Women Loving Women

During her lifetime, friends and media coverage described the artist Harriet Hosmer as “eccentric”, “peculiar,” and “singular.” As a child, she was called a “tomboy.” She wore what clothes she wished, regardless of fashion, walked through cities at night unaccompanied, and throughout her life, flirted and fell passionately in love with women. While intimate friendships were common for young women of her generation, Harriet made it clear that some relationships were different.

For decades, Hosmer lived as a family with Lady Louisa Ashburton and her daughter in Europe. To Lousia, Harriet wrote, “When you are here, I shall be a model wife (or husband, whichever you like),” and over the years called her sposa (spouse), hubby, and beloved. Harriet’s relationships with women were not a secret to friends and family. As scholar Leila Rupp notes in Sapphistries: A Global History of Love between Women, “…women who loved or desired other women found ways, since the earliest recorded history, to be together.”

By 1908, when Harriet died, society began to view same-sex couples in a negative way. Doctors in the new field of sexology began to label some relationships as sexual inversion or perversion. So in 1912, when Cornelia published Harriet Hosmer: Letters and Memories, she told the essence of Harriet’s life story, with careful edits to ensure there was no suggestion of improper relationships. Yet, Cornelia also ensured that the original letters and documents of Hosmer’s life were saved, allowing contemporary historians to tell the full story of these women’s lives.

From Schoolgirls to Chosen Family

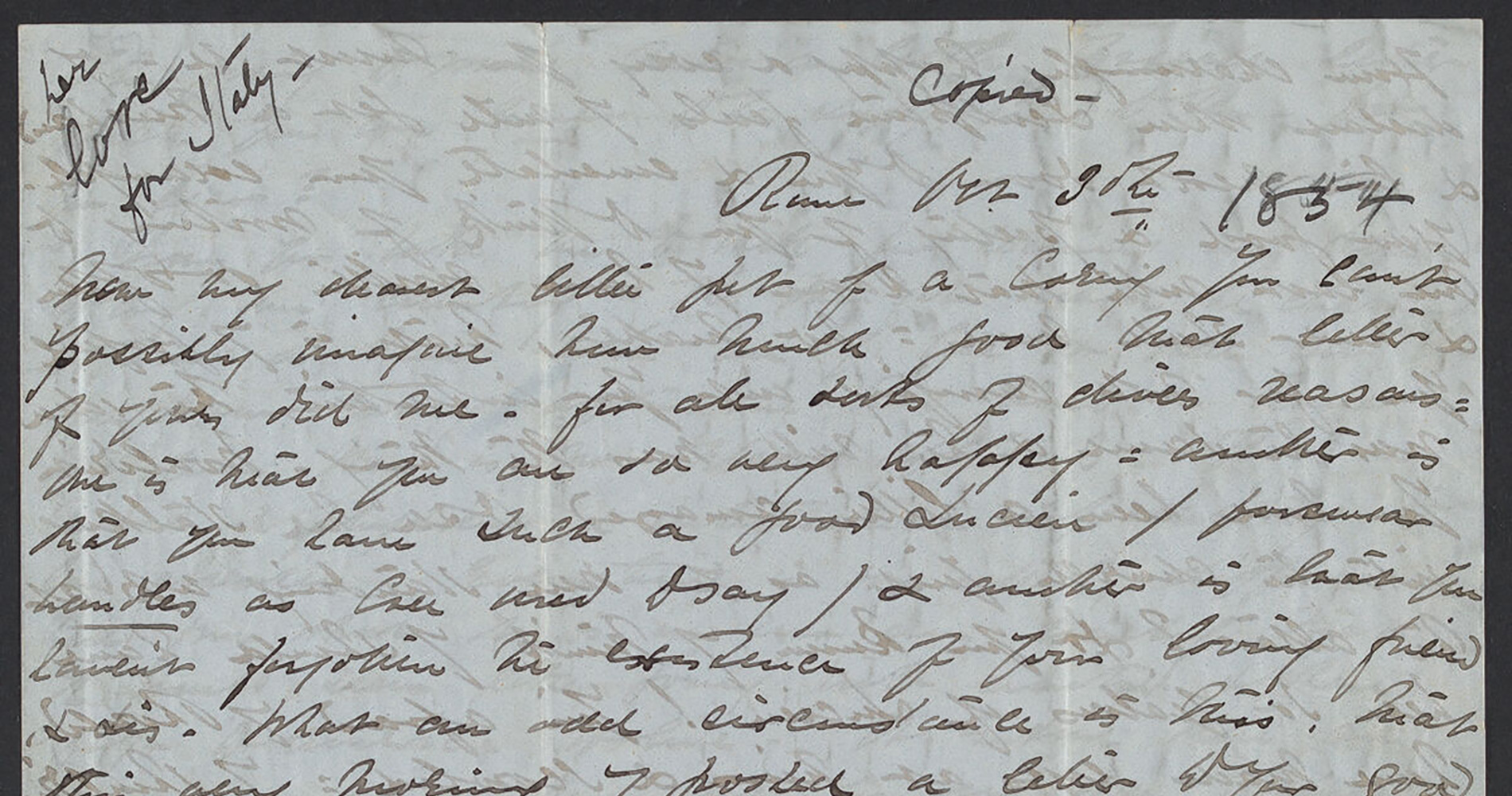

Hosmer was infatuated upon meeting Cornelia in school, and somewhat heartbroken when her “Cornie” married a young man in St. Louis, Lucian Carr. Nevertheless, their close relationship persisted. Cornelia named her firstborn child Harriet “Hatty” Hosmer Carr, selecting her dear friend as godmother. This delighted the elder Hosmer, who wrote the child’s father in 1853, “Having written to your little daughter and my goddaughter, I am going to send you this note in her care …. And how is Nelly [Cornelia]? Doubly happy of course now that she has a little daughter. I can fancy the mother she makes for I have had opportunities of proving her tenderness and loving kindness and I envy my little Hatty the care and love she will have bestowed upon her. …” Hosmer ended the letter, “Kiss her for me continuously & take a kiss for yourself if you like from your loving hat [Harriet].”

This letter, currently on exhibit, is one of many documents and books saved by Cornelia. After she died in 1922, they passed down through the family to Polly, Cornelia’s great-granddaughter. In 2021, Polly’s brother Andrew Leighton inherited them and chose to return them to St. Louis at the archives of Washington University.

The Crow Carr Family Papers, with 130 books and 10 boxes of correspondence, photographs, keepsakes, and newspaper clippings, are available to researchers at the Julian Edison Department of Special Collections at Washington University Libraries. A full catalog of the contents is listed online.

Also featured in the exhibition is Hosmer’s Daphne, on loan from the Mildred Kemper Art Museum. The marble sculpture was completed in Rome as a gift for Cornelia and the Crow family, who were her financial backers. Shipping it to St. Louis in 1854, Hosmer wrote, “…when Daphne arrives kiss her lips and then remember that I kissed her just before she left me. I hope you will like her and look upon her as a blood-relation.”

The sculpture remained in the Crow family until 1880, when it was donated to the collections of Washington University. As a nineteenth-century work, Daphne is not often on public view. This exhibit offers visitors a rare opportunity to see not only Hosmer’s earliest work, created in Rome, but also to view it in context with the letters and books contemporaneous with its creation.

For more information on the exhibition, visit Intertwined Lives: Harriet Hosmer and Cornelia Crow Carr.

Explore further with books available via WashU Libraries:

Culkin, Kate. Harriet Hosmer: A Cultural Biography (Boston: U of Mass. Press, 2010)

History Project. Improper Bostonians: Lesbian and Gay History from the Puritans to Playland. (Beacon Press, 1998)

Markus, Julia. Across an Untried Sea: Discovering Lives Hidden in the Shadow of Convention and Time (NY: Knopf, 2000)

Merrill, Lisa. When Romeo Was a Woman: Charlotte Cushman and Her Circle of Female Spectators (U of Michigan Press,1998)

Rupp, Leila. Sapphistries: A Global History of Love between Women (NYU Press, 2009)

Vicinus, Martha. Intimate Friends: Women Who Loved Women, 1778-1928. (U of Chicago Press, 2004)